franzi-img_0290entzerrt-kl

Franziska Lesák + Ricarda Denzer

Gray Area

Text by Franziska Lesák

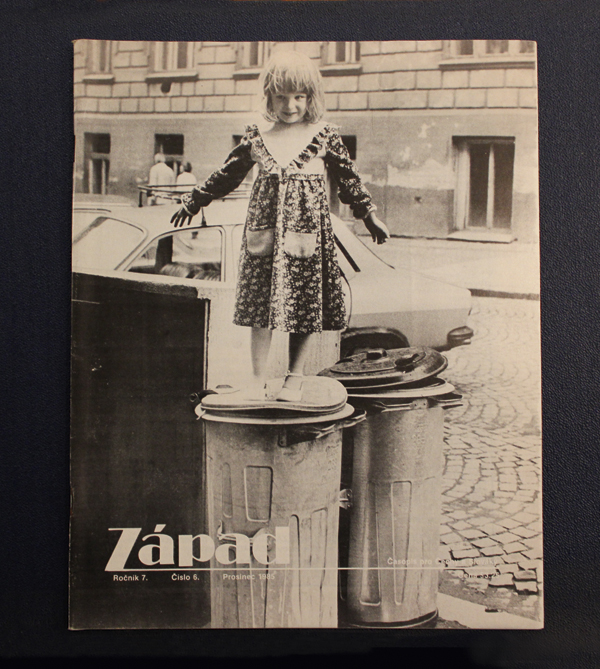

Notes on “commitment” in the arts in communist Prague

The exhibition ‚Other Possible Worlds—Proposals this Side of Utopia‘ has its correlation in the historic example of the fate of the arts scene in Czechoslovakia during communism. It illustrates how parallel structures emerged where scientific and artistic progress could thrive.

The follow-up to the suppression of the Prague Spring of 1968 reverberated everywhere and with particular severity amongst the critically minded part of the population. It destroyed any hopes for socialism with a human face. The subsequent years were characterized by a period of “neutralization.” Many intellectuals were forced to emigrate, some remained as dissidents, and others preferred a state of internal migration. Most could no longer work in their professions and had to survive on menial labor.

Against this background a parallel and independent artistic subculture emerged whose protagonists attempted to continue working in spite of the repressions. Evening universities [1] operated underground, establishing their own structures of assembly and dissemination. Writers and researchers would publish work in unofficial ‚Samizdats‘.[2] Exhibitions and concerts were organized privately and in non-institutional locations. Lifestyles and working methods of dissent [3] arose which are reclaiming their relevance for today’s important and innovative context of arts projects staged in self-organized spaces, academies, laboratories and distribution networks, as seen in this exhibit ‚Other Possible Worlds‘.

Curator and architectural theoretician Jiší Ševšík describes his experience with independently-organized structures: “Basically the rift with conventional society can be dated back to the year 1948. Intellectual circles nevertheless insisted on maintaining contact via documents, books, text, etc. The fifties and sixties were hence part of our destiny. They are part of our experience, which has to some extent been an original one, something that has determined the attitudes of generations. In the post totalitarian era of the seventies it meant having to resort to a non-official level, to a kind of alternative subculture.” [4] He continues to describe these events in more detail: “In the late nineteen seventies, we organized many exhibitions at alternative venues. Usually these were the cultural houses in the periphery of Prague where it was possible to put up shows at short notice.” [5]

Všra Jirousová describes the ingenuity required to present work to an interested audience: “In the nineteen sixties and seventies I made friends with Olga Karlíková, who’d always be in the company of Václav Havel. She was one of these eccentric personalities who always did whatever she felt like doing. Emotion and action are always symbiotically linked in her work—something she herself only saw later. Olga Karlíková too was not officially allowed to show and that’s why she was looking for out-of-town spaces or participated in clandestine improvised shows in private Prague studios.” [6]

Jirousová’s description mirrors the kinds of activities that continue to be driven by the contemporary arts scene in the Czech Republic and elsewhere in western Europe. “It was impossible to mount official art shows in the seventies. That’s why exhibitions took place clandestinely in private flats or artist’s studios. Communication spread privately amongst friends. There was a lot of improvisation in private homes, where we mounted exhibitions and also theatrical events, seminars and concerts… Rock’n Roll was as commonplace for us as popular music is important for today’s youth. Music was a means of feeling close. You needed to be really crafty to arrange all the activities around the group ‚Plastic People of the Universe‘. We camouflaged gigs as musical wedding performances or played on boats. We organized festivals insisting on choosing our own music. These concerts happened in secret, on Mount Blaník for instance, or as part of an event run by unofficial artists’ collective, Knights of the Cross.” [7]

Jiší Gruntorád, one of the co-founders of ‚Libri Prohibiti‘ [8] in Prague, remembers: “I stumbled across Samizdat literature accidentally in 1978 at Václav Benda’s (later spokesperson for Charta 77) place, and I realized that that was the perfect solution to counter the shortage of good literature. It took just ten to fifteen privately made machine written copies to publish the work of the very best Czech authors for a wider audience.” [9]

– –

[1] cf. working documents and material at Forschungsstelle Osteuropa, Bremen.

Nr. 100: Karoline von Gravenitz, Die Untergrunduniversität der Prager Bohemisten. Ein Fallbeispiel für Parallelkultur in der normalisierten CSSR, 2008.

[2] Samizdat (Russ., to publish) independently published text, magazines and literary works by forbidden authors and disseminated privately. cf. Ivo Bock, “Der literarische Samizdat nach 1968,” Samizdat. Alternative Kultur in Zentral- und Osteuropa: Die 60er bis 80er Jahre, ed. Wolfgang Eichwede, Bremen, 2000, pp 68–93

[3] I recommend this comprehensive selection of programmatic and scientific texts, which give an excellent insight into conditions of artistic production and during the phase of Neutralization: Utopien und Konflikte. Dokumente und Manifeste zur tschechischen Kunst 1938–1989, ed. Jiší Ševšík, Peter Weibel, exh. cat. ZKM, Karlsruhe, 2007.

[4] Quoted from an interview with Jiší Ševšík (theoretician, curator and head of the Research Institute of the Academy of Fine Arts, Prague). His and other memoirs will be published in book form and on DVD in summer 2011, within an interdisciplinary research project on transformation in eastern Europe, citing the example of Prague, and in collaboration with artist Ricarda Denzer, (with generous support from ERSTE Stiftung, Vienna).

[5] ibid.

[6] Quoted from an interview with Všra Jirousová (art historian, curator, writer), cf. note 4

[7] ibid.

[8] Library founded in 1990 to collect forbidden books, publications and periodicals published underground during the communist era.

[9] Quoted from the interview with Jiší Gruntorád, cf. note 4